“Why is the sky blue?”, wonders Maggie Nelson in her hybrid prose poem Bluets (2009). In search for answers, the author remembers that the colour of any planetary atmosphere viewed against the black of space and illuminated by a sunlike star will appear blue. In an anecdote in Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project (1927–40), a child looks in awe at a panoramic painting, remarking “it’s only too bad that the sky is so dreary” to which his mother responds, “that’s what the weather is like in war”. It’s precisely this gloomy sky and its political landscape that Flaka Haliti’s exhibition Partly Cloudy or Partly Sunny at Deborah Schamoni is centred on.

read more

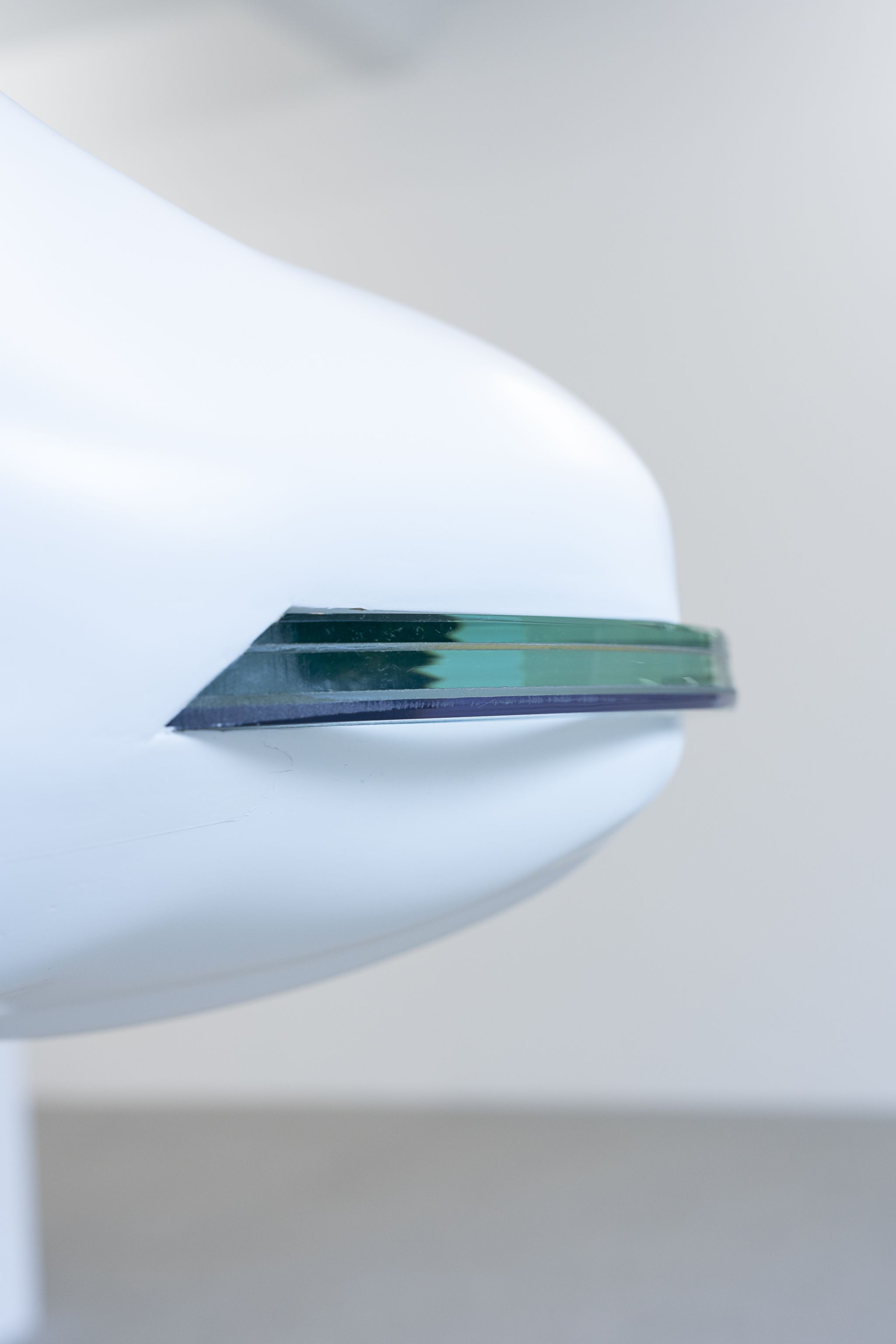

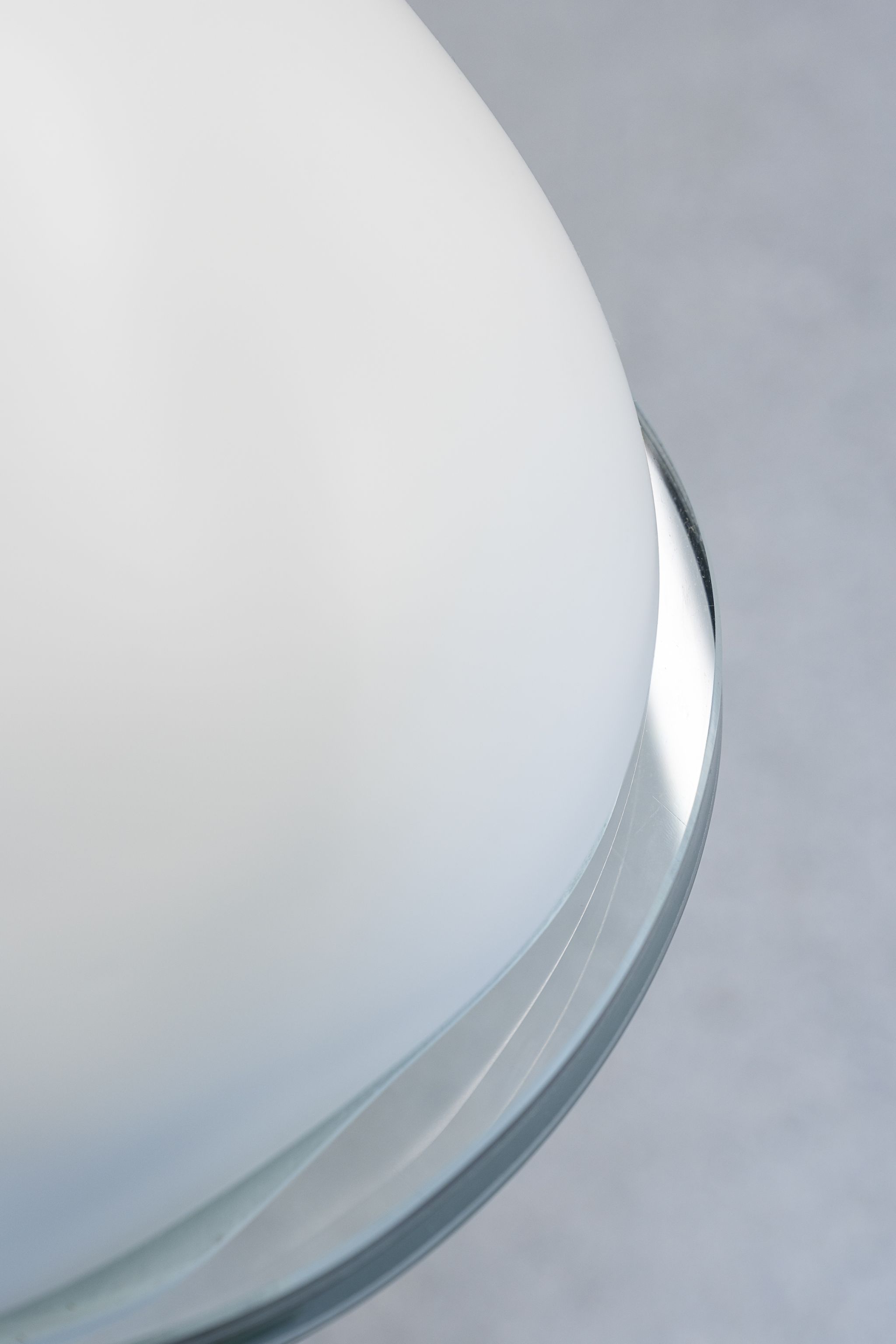

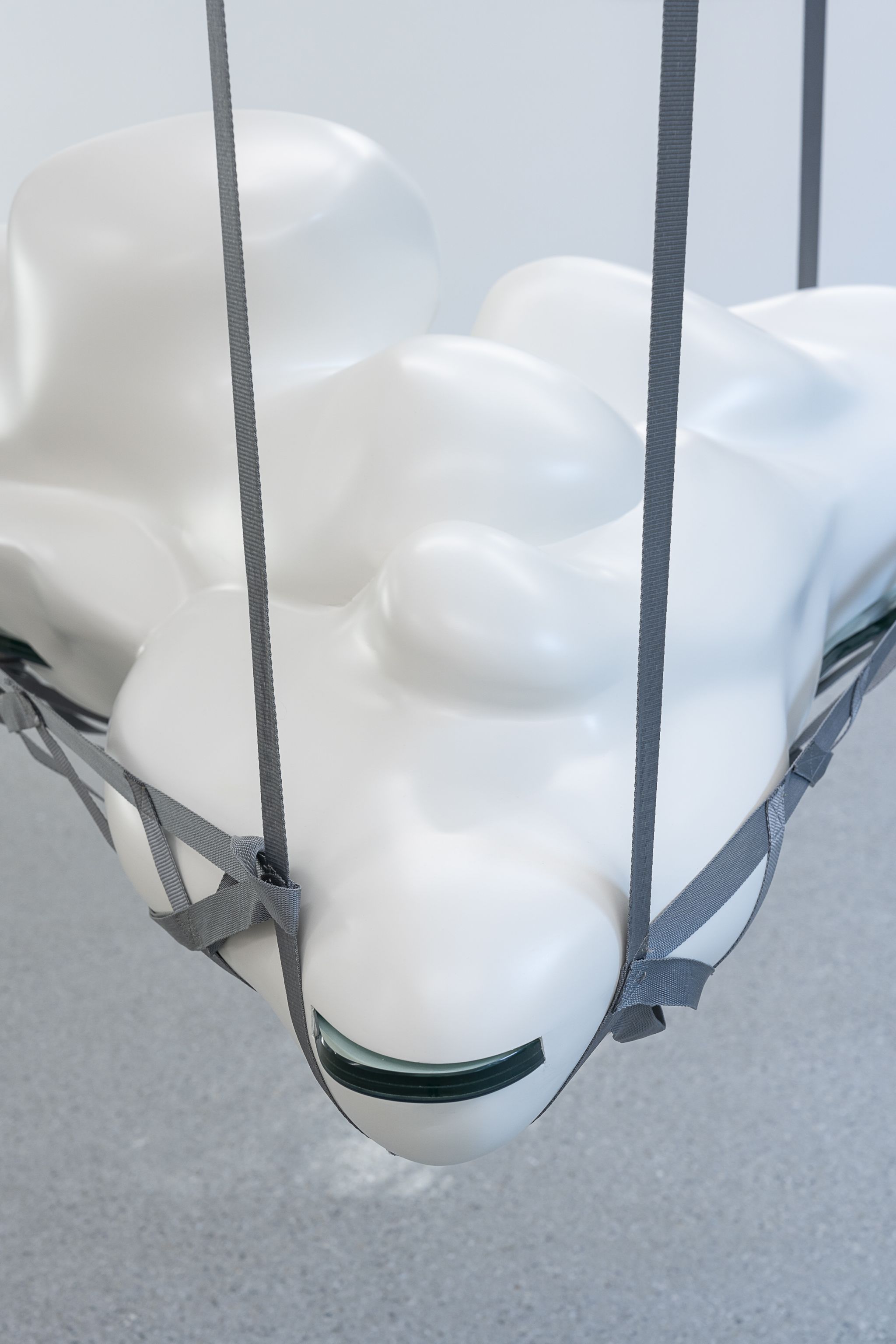

In many ways, Haliti’s exhibition can be understood as a continuation of her ongoing investigation into what she terms the “demilitarisation of aesthetics”, challenging the pervasive influence of military aesthetics on societal structures and collective consciousness. Rooted in the lived experience of the Kosovo War (1998–99) and emerging from the shadows of the nation’s fraught history with NATO’s peacekeeping forces, Haliti’s works often incorporates or directly references materials sourced from the visual vocabulary of defence forces. At the centre of her show is the eponymous sculpture Partly Cloudy or Partly Sunny (all works 2024), a lacquered cloud modelled from wood sitting between bulletproof glass and suspended from the ceiling with a military cargo net. Not only does the work call to mind Haliti’s earlier photo series of clouds I See a Face. Do You See a Face.(2014) but its title is also a reference to the inherent contradictions of the work: the fluidity and formlessness of the cloud juxtaposed with the solidity and violence of the materials used to create it.

While Haliti’s earlier works(1) considered how the colour blue serves as a social code of unified Western values – indicated by its use in flags of international bodies like the European Union and the United Nations – here it is not the blue sky but the blurry cloud that signifies tactics of obstruction during war. For The Emperor Was Extremely Chatty, the artist enlarged an image of the dreary sky in Anton von Werner’s Sedan Panorama (1883) and printed it on separate metal plates. Originally installed at Berlin’s Alexanderplatz as a massive canvas of 1735m², the panorama depicts the Battle of Sedan (1870) at a decisive moment in the victory of the German forces over the French. Giving the illusion of a rotunda, the shape not only draws on architecture of control and the ways in which the original panorama – in its sheer size and prominent placement – intended for the audience to be immersed into a collective experience of war, but also on W.J.T. Mitchell’s concept of the meta-picture: images that expose their own conditions of possibility or problematise the act of representation itself.

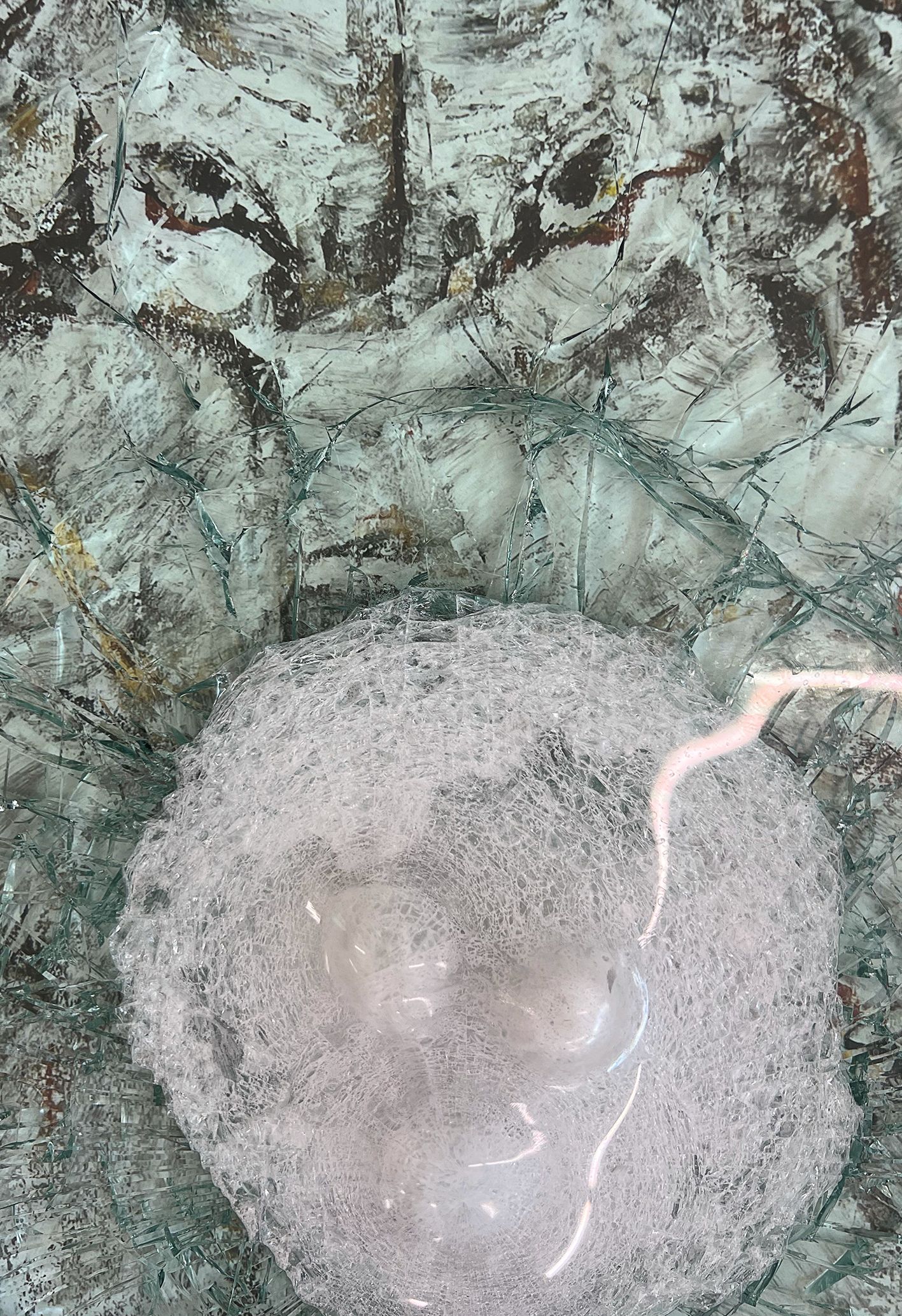

Conversely, the motifs of the drawings in Empty but Present, Absent but Full only reveal themselves while looking past the bulletproof glass at which various bullets have been fired: a horse’s head and a dog’s snout, symbols of animals historically exploited in warfare. By placing the drawings behind the glass, Haliti alludes to the urge to recognise the gap between an image’s form and its deeper, constructed meaning – what Roland Barthes referred to as contemporary myth – which reinforces dominant ideologies by disguising them as universal truths.

Throughout the last two centuries, the rhetoric surrounding empires has evolved in tandem with their decline. However, what has endured – and what Haliti’s exhibition attests to – is the persistent use of military power to assert dominance. In Partly Cloudy or Partly Sunny, she seems to suggest that one way to challenge the persisting entanglement of aesthetics and warfare that governs contemporary societies is by means of ambiguity and abstraction – strategies that disrupt prevailing myths and narratives of power and dominance. Throughout her work, Haliti offers a potent reminder of art’s potency to reimagine a collective future rather than merely echo the current state of affairs. As a result, perhaps in future, we might ask not why the sky is blue, but rather, why it is partially cloudy and sunny, calling for a more nuanced and complex view of the world.

Text: Carina Bukuts

(1) The most prominent example is likely to be the installation Speculating on the Blue (2015), presented at the Kosovo Pavilion at the 56th La Biennale di Venezia, for which she covered the floor with blue sand and metal constructions resembling border wall supports. Experimenting with the concepts of visibility and invisibility, the light colours shifted throughout the day – from white to yellow, red, pink and finally blue – to alter the viewer’s perception and evoke disorientation, symbolizing the psychological and physical barriers of national borders.

The exhibition is generously supported with glass panels by ISOCLIMA.

„Why is the sky blue?“, fragt sich Maggie Nelson in ihrer hybriden Prosa Bluets (2009). Auf der Suche nach Antworten erinnert sich die Autorin daran, dass die Farbe jeder planetaren Atmosphäre, die vor dem Schwarz des Weltraums und unter der Beleuchtung eines sonnenähnlichen Sterns betrachtet wird, blau erscheint. In einer Anekdote aus Walter Benjamins Passagen-Werk (1927–40) betrachtet ein Kind ehrfürchtig ein Panoramabild und bemerkt: „Nur schade, dass der Himmel so trübe ist“, woraufhin seine Mutter erwidert: „So ist das Wetter im Krieg.“ Genau dieser düstere Himmel und seine politische Bedeutung stehen im Fokus der Ausstellung Partly Cloudy or Partly Sunny von Flaka Haliti in der Galerie Deborah Schamoni.

read more

In vielerlei Hinsicht kann Halitis Ausstellung als Fortsetzung ihrer laufenden Untersuchung dessen verstanden werden, was sie als „Entmilitarisierung der Ästhetik“ bezeichnet. Dabei hinterfragt sie den allgegenwärtigen Einfluss militärischer Ästhetik auf gesellschaftliche Strukturen und das kollektive Bewusstsein. Verwurzelt in den Erfahrungen des Kosovokriegs (1998–99) und geprägt von der schwierigen Geschichte des Landes mit den NATO-Friedenstruppen, beziehen Halitis Werke oft Materialien aus dem visuellen Vokabular der Streitkräfte ein oder nehmen direkt darauf Bezug. Im Mittelpunkt ihrer Ausstellung steht die gleichnamige Skulptur Partly Cloudy or Partly Sunny (alle Werke 2024), eine lackierte Wolke aus Holz, die zwischen kugelsicherem Glas schwebt und an einem Militärfrachtnetz von der Decke hängt. Das Werk erinnert nicht nur an Halitis frühere Fotoserie von Wolken I See a Face. Do You See a Face. (2014), sondern der Titel verweist auch auf die inhärenten Widersprüche des Werks: die Leichtigkeit und Formlosigkeit der Wolke im Gegensatz zur Stabilität und Bedrohlichkeit der verwendeten Materialien.

Während Halitis frühere Arbeiten(1) untersuchten, wie die Farbe Blau als soziales Symbol für vereinheitlichte westliche Werte dient – angedeutet durch ihre Verwendung in Flaggen internationaler Organisationen wie der Europäischen Union und den Vereinten Nationen –, steht hier nicht der blaue Himmel, sondern die diffuse Wolke für Taktiken der Verschleierung im Krieg. Für The Emperor Was Extremely Chatty vergrößerte die Künstlerin ein Bild des trüben Himmels in Anton von Werners Sedan-Panorama (1883) und druckte es auf einzelne Metallplatten. Ursprünglich am Alexanderplatz in Berlin als riesige Leinwand von 1735 m² installiert, zeigt das Panorama die Schlacht von Sedan (1870) in einem entscheidenden Moment des Sieges der deutschen über die französischen Streitkräfte. Die Form, die die Illusion einer Rotunde erzeugt, verweist nicht nur auf Architekturen der Kontrolle und darauf, wie das ursprüngliche Panorama – durch seine schiere Größe und prominente Platzierung – das Publikum in ein kollektives Kriegserlebnis eintauchen lassen sollte, sondern auch auf W.J.T. Mitchells Konzept des Meta-Bildes: Bilder, die ihre eigenen Entstehungsbedingungen offenlegen oder die Art und Weise ihrer Darstellung selbst hinterfragen.

Im Gegensatz dazu werden die Motive der Zeichnungen in Empty but Present, Absent but Full erst beim Blick durch das kugelsichere Glas erkenntlich, auf das verschiedene Kugeln abgefeuert wurden: ein Pferdekopf und eine Hundeschnauze, Symbole für Tiere, die historisch im Krieg ausgebeutet wurden. Durch die Platzierung der Zeichnungen hinter Glas verweist Haliti auf die Notwendigkeit, die Kluft zwischen der äußeren Form eines Bildes und seiner tieferen, konstruierten Bedeutung zu erkennen – was Roland Barthes als zeitgenössischen Mythos bezeichnete, der herrschende Ideologien verstärkt, indem diese als vermeintlich universelle Wahrheiten dargestellt werden.

Im Laufe der letzten zwei Jahrhunderte hat sich die Rhetorik rund um Imperien parallel zu ihrem Niedergang entwickelt. Was jedoch fortbesteht – und was Halitis Ausstellung deutlich macht –, ist der anhaltende Einsatz militärischer Macht, um Vorherrschaft zu sichern. In Partly Cloudy or Partly Sunny scheint sie anzudeuten, dass eine Möglichkeit, die anhaltende Verstrickung von Ästhetik und Kriegsführung, die unsere heutigen Gesellschaften prägt, herauszufordern, in dem Einsatz von Ambiguität und Abstraktion liegt – Strategien, die vorherrschende Mythen und Erzählungen von Macht und Dominanz unterbrechen. Durch Halitis gesamtes Werk zieht sich ein eindringlicher Appell an das Potential der Kunst, eine kollektive Zukunft neu zu denken, anstatt nur die aktuellen Gegebenheiten widerzuspiegeln. Als Konsequenz darauf fragen wir uns in Zukunft vielleicht nicht mehr, warum der Himmel blau ist, sondern warum er teils bewölkt und teils sonnig ist, was zu einer nuancierteren und komplexeren Sicht auf die Welt anregt.

Text: Carina Bukuts

(1) Das bekannteste Beispiel ist wahrscheinlich die Installation Speculating on the Blue (2015), die im Pavillon des Kosovo auf der 56. Biennale von Venedig gezeigt wurde. Für diese Installation bedeckte sie den Boden mit blauem Sand und Metallkonstruktionen, die den Stützen einer Grenzmauer ähneln. Indem sie mit den Konzepten von Sichtbarkeit und Unsichtbarkeit experimentierte, wechselten die hellen Farben im Laufe des Tages – von Weiß zu Gelb, Rot, Pink und schließlich Blau. Dies veränderte die Wahrnehmung der Betrachter und erzeugte Desorientierung, was die psychologischen und physischen Barrieren nationaler Grenzen symbolisiert.

Die Ausstellung ist grosszügig mit Glasplatten unterstützt von ISOCLIMA.