-

Since the 1990s, Berlin-based artist Judith Hopf has mastered an independent artistic language that unswervingly manages to stake out new ground, be it in the form of sculpture, film, drawing, performance, or stage design. Her iconic works are deeply rooted in the use of everyday materials, such as brick, concrete, glass, or packaging, and easily graspable manufacturing processes, employing them to investigate the social dynamics of our built environment and their influence on behavior, power dynamics, and social codes.

read moreThe exhibition Stepping Stairs confronts the faceless creations of modern life by taking a closer look at the objects that so elegantly shape our daily routine, whilst responding to the effect that advances in economics and technology have had on our bodies and mental compositions. The title Stepping Stairs derives from a text written by Hopf in which she recalls the moments where life feels like climbing upstairs against the flow of a descending escalator. In the exhibition, Hopf references two likeminded artists and inspirations: the American architect and architectural theorist John Hejduk (1929–2000), and the German artist, and former colleague of Hopf, Annette Wehrmann (1961–2010), identifying in both of their works an appeal to “chatter away against automatic knowledge in general and against greyness in particular”. For Hejduk, this is especially relevant in his Berlin Masque building complex in Berlin-Kreuzberg, with its grey walls and olive-green steel balconies and sunshades, while in Wehrmann’s case, Hopf sees this in her colorful and unruly “serpentine streamer”.

The exhibition compiles a survey of Hopf’s practice by bringing together new commissions alongside older bodies of work. Upon entering, the visitor is greeted by a reworked group of Hopf’s laptop sculptures Untitled (Laptop Men) (2018) scattered across the lower ground floor. Abstract figures, like line drawings but made of sheet metal, are positioned in different everyday poses and appear to be seamlessly merged with the laptops they balance on their waists and knees. Shaped by what appears to be an over-use of technology, the sculptures assume a hybrid form situated somewhere between laptop and human being. Hopf makes a humorous reference to the way we depend on our devices and the growing tendency to perceive them as part of our bodies.

The lingering gray bodies are framed by Hopf’s Untitled (Email Lines) (2016), three colored LED light chains suspended from the ceiling. They present a physical manifestation of the seemingly endless back and forth conversations that we carry around dematerialized on our devices. Untitled (Email Lines) questions how communication can be defined nowadays, especially in regards to the relationship between work and leisure, since both are widely pursued through the same device.

The video Lily’s Laptop (2013) plays in a loop, a homage to the 1911 film Le Bateau de Léontine (Betty’s Boat) by Roméo Bosetti. The film shows the au pair Lily flooding the modernist home of her employers. To determine whether her laptop is able to swim, she turns on the faucets and leaves the household under water until all belongings are washed away in a slapstick-like gesture.

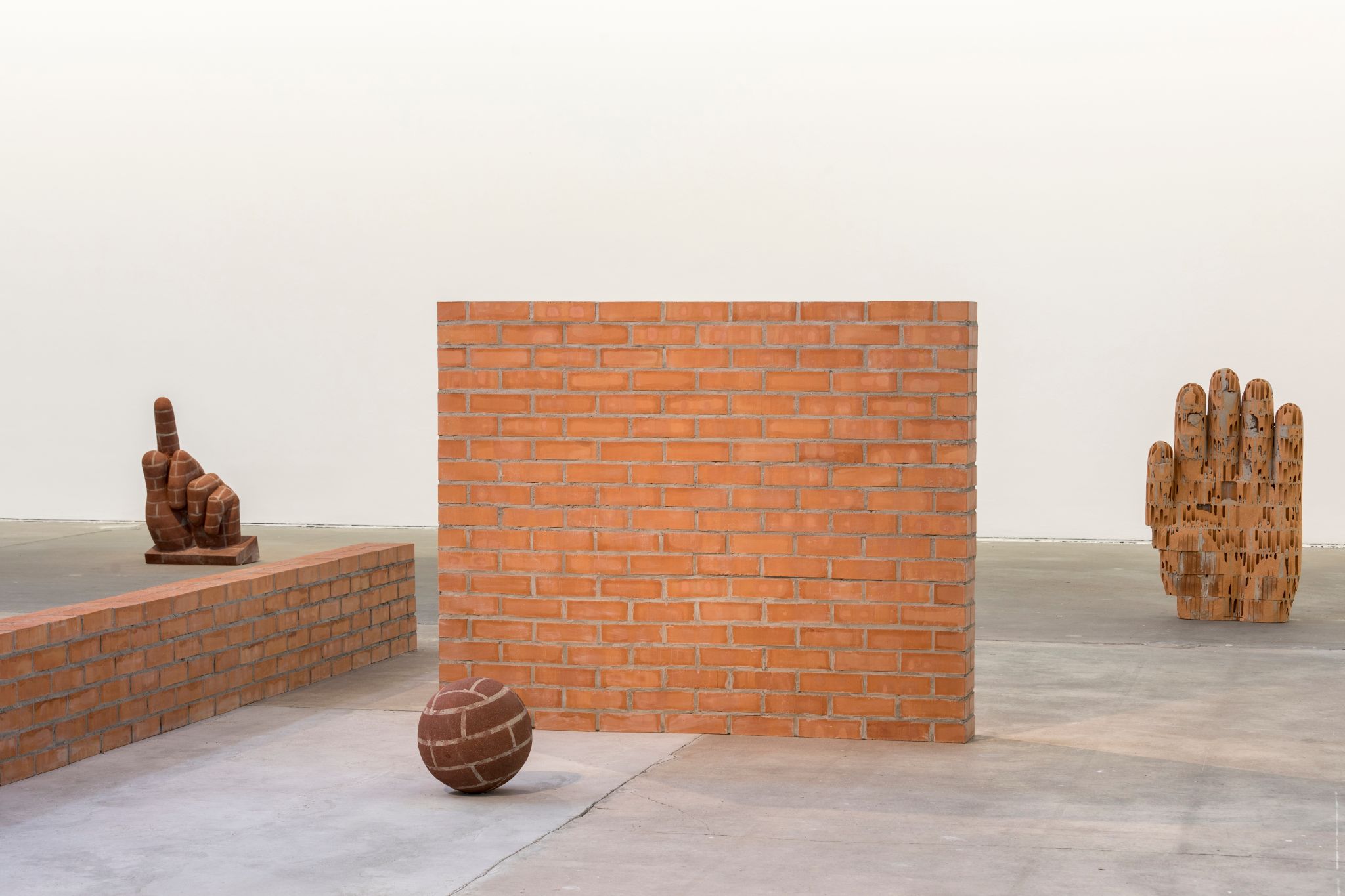

For her installation in the main hall of KW, Hopf continues her recent fascination with bricks. The masoned brick works occupy a curious intermediary position that fluctuates between sculpture and (exhibition-) architecture, both dividing and augmenting the exhibition space. Lower and higher walls structure the hall and are interspersed with objects made from bricks. One encounters oversized brick hands (Hand 1, 2, 3, 4, 2016–17) that appear to be signaling emphatic yet ambiguous messages to the visitor, brick balls (Ball in Remembrance of Annette Wehrmann, 2016), and a new series of giant brick pears (Birnen, 2018). In the older works, industrially fired bricks were formed into cubes, and then shapes were hewn out of them. For the new series of pears, the cubes have been industrially cut into pear shapes. In each process, there appears to be a curious reversal at play, which turns a geometrical abstract form in the tradition of minimal art into an illusionary shape that mimics anthropomorphic traits. Her sculptures resist the sleekness of the newest production methods and make easy circulation and distribution impossible through their laborious production method and sheer weight. Here, process has to be understood as a political stance against the demand for acceleration, a gesture that is often mirrored in the anthropomorphic attitudes and laconic expressions of her hybridized objects.

Two films are housed in Hopf’s unique floating cinemas, black tent-like cloth structures hanging in the exhibition space, and which the audience must plunge into to enter. For the film Türen (2007, together with Henrik Olesen) Hopf and Olesen restaged a scene from Luis Buñuel’s film Le Fantôme de la liberté (The Phantom of Liberty, 1974) in which different doors open on to a variety of little vignettes that take place behind them. Here, in a choreography of comedic gold, a series of chance meetings take place in a corridor where people from different backgrounds meet for brief absurdist encounters before they disappear again behind their respective doors.

In her new film OUT (2018), we are faced with the question: How can one type of architecture enter another? Both films, like much of Hopf’s work, defy the conformity demanded by the need for perpetual progress, calling for resistance both through overt malleability and bulkiness as well as through the transferral of overly human qualities like stupor, embarrassment, stupidity, and exhaustion onto the objects she creates.

At its very end, the exhibition spills out into the KW courtyard in the shape of a permanent commission for the left side of the building’s façade. A cheekily anthropomorphized face can be recognized in the Hejduk-like sunshades, paired with a long red tongue and a blonde mop of hair that reaches into the courtyard like a ray of sunshine. Her gesture to animate the inanimate imbues it with the potential for purpose and agency.

As part of the supporting program, an installation of Annette Wehrmann’s Serpentine Streamers and an audio recording of the artist reading the texts will be presented on KW’s 3rd floor. Wehrmann typed her texts, which unite everyday observations with philosophical and aesthetic inquiries, onto serpentine streamers. In her performances, she creates visual poetry in space, reflecting on art in a social context.

The exhibition is accompanied by a comprehensive reader edited by Anna Gritz and co-published with Koenig Books. The publication includes texts and contributions by Kathy Acker, Madeleine Bernstorff, Sabeth Buchmann, Maurin Dietrich, Anna Gritz, John Hejduk, Judith Hopf, Monika Rinck, Avital Ronell, and Annette Wehrmann.

Curated by Anna Gritz

Assistant Curator: Maurin Dietrich

Text: KW Institute for Contemporary Art

Photos: Frank Sperling and KW Institute for Contemporary Art

Wednesday – Friday 12 – 6 pm

Saturday 12 – 4 pm and by appointment

-

Since the 1990s, Berlin-based artist Judith Hopf has mastered an independent artistic language that unswervingly manages to stake out new ground, be it in the form of sculpture, film, drawing, performance, or stage design. Her iconic works are deeply rooted in the use of everyday materials, such as brick, concrete, glass, or packaging, and easily graspable manufacturing processes, employing them to investigate the social dynamics of our built environment and their influence on behavior, power dynamics, and social codes.

read more